Before you get too excited, no, veteran actor Daniel Day-Lewis is not planning to star in a film of the 1930s Aldous Huxley classic. But Huxley’s book title would have been an aptly-titled description of Daniel Day-Lewis’s visit to Gaza seventy years later in 2005; at least, according to ‘Honest Reporting’ and other media-monitoring journals, who felt that Daniel DL’s report ‘lacked balance’, since he hadn’t bothered to also report on conditions in Sderot, just the other side of the Gaza border in Southern Israel.

So I thought it would be an interesting exercise to have an article, as if Daniel DL had in fact made good on that suggestion by returning to the area years later to give an account of findings in Sderot. (Let me repeat that, because it could be missed on a quick read: this is not an actual report from Daniel DL himself, merely a projected article, as if he, or his alter-ego, or a fellow actor (or writer, like myself) had visited Sderot – to give more balance to his earlier article).

However, the details provided here are accurate for the period concerned, many of them taken from existing reports and eye-witness accounts from Sderot and Gaza; and in many ways, because it gives a view of both sides of the conflict in the area, might be seen to be more accurate than his original report; or certainly more ‘balanced’, which has been the main aim here.

The article is written in the same first-person, observant style as the original article (which can be read on the link below):

www.ngo-monitor.org/_inside_scarred_minds_/

My guide is Gerry, originally from Dublin, who has been working with Christian Aid for many years in Sderot. One of the first places we visit is a home on the southern edge of the town, a modest bungalow which was hit by a Kassam rocket just a month ago.

The owners of the house, Morris and Sara, point to the dining-room roof where the Kassam hit. It has been patched up now, but the damage-area is clear, a hole seven-foot-wide – although the flying shrapnel, plaster, masonry and glass from the blast spread far wider.

Their son, Ben, only eight, points to the wound on his arm from some of the shrapnel. He smiles uncertainly; proud, but not proud. His younger brother, Avi, only four, wasn’t so lucky. A flying chunk of masonry crushed his left leg. After three months of operations, doctors were left with no choice but to amputate the leg beneath the knee joint. A wheelchair stands in the corner as testament to his injury. Morris casts his eyes down.

‘We were outside when we heard the rocket alert. We weren’t able to get the boys to a shelter in time.’

It’s as if Morris blames himself as much as the people firing the rockets. Morris was also hit by shrapnel, but he shrugs, doesn’t want to make anything of it, take anything away from Avi’s more serious injury.

Gerry tells me that many minor injuries in Sderot go unreported. But even with the number that are reported, the total injured in Sderot and the surrounding area from rocket and mortar attacks from Gaza now reaches almost 2,000 – on top of the 44 killed from attacks.

Gerry informs me that the population of Sderot is only 19,000, dropped from 24,000 a few years ago, mainly because of the constant rocket attacks. I do a quick calculation: that’s one in ten people injured due to rocket attacks! A staggering proportion.

We see that painfully evident as I visit other families with Gerry. Nearly everyone knows someone who has been injured by rocket attack, many of them family or close friends. Then we visit Ben’s school, followed by two more local schools. Another boy in Ben’s class lost an eye from flying shrapnel in a rocket attack last year, and at the second school visited a boy was killed eighteen months ago. In line with that one-in-ten ratio I’ve calculated, we are availed of numerous other horror stories in each school ranging from minor disfigurements to lost limbs. And, of course, deaths.

At the last school on our list, the red-alert sirens sound before we’ve hardly started our discussions with teachers, pupils and invited parents. Everything is suddenly pandemonium. A mad rush, children first, as we’re all shepherded to the bomb shelter at the far end of the playground.

Everyone’s silent inside the shelter, expectant, as if holding collective breath, the continuing siren outside smothering our thoughts. Then finally we hear a distant boom and bang, then one far sharper, closer – no more than a couple of hundred yards away. Then nothing except the siren again. The children look terrified.

The siren in fact continues for another twenty minutes before finally stopping and we all emerge.

As if in apology for the sudden rush, one of the teachers comments, ‘We only get fifteen seconds warning, I’m afraid. Often it’s not enough to get all the children rallied from the classrooms and into the shelter in time.’ She shrugs helplessly. ‘But what can you do? The rockets are being fired from so close by.’

‘How often do you get siren warnings?’ I ask.

‘Five or six a week. Sometimes that many in a single day.’

One of the parents complains that many of the rockets are aimed at schools, ‘And often at school-run times in the morning or afternoon. It’s as if they purposely want to catch the kids and parents on the hop, unable to get to shelters on time.’

The children’s fear stays on my mind. Uncertain looks punctuated by uneasy smiles, wondering whether they might be next to lose an eye or a limb, or their lives.

The clinical psychiatrist I meet the next day, Elena, explains that it’s not just the fear of possible injury or loss of life, ‘But the daily noise of the sirens as a reminder, along with the pressure to get to a shelter in time. All of that takes a terrible toll on the people of Sderot, but particularly the children.’

Elena has worked for the past five years attached to Sderot’s Medical Health Center. She passes me some statistics to read. They’re truly shocking: 65 percent know someone who was physically injured by a rocket; 48 percent know someone who has died in a rocket attack; 74 percent of children between the ages of 7 and 12 suffer intense fear; 86 percent of children between the ages of 12 and 14 suffer from post-traumatic stress.

‘But it’s not just the young who are very vulnerable, but the elderly too. Let me show you an example.’

We go in Elena’s car to see an elderly couple two miles from her office. Ivan and Lena survived the holocaust to settle in Israel, and moved to Sderot ten years ago to be near their daughter, an administrator with a local kibbutz. Their house is modest and basic, few frills.

Elena goes on to explain that many people on minimum income, such as Ivan and Lena, can’t afford either bomb shelters or to have their whole house fortified. ‘All they can afford, and even that with government assistance, is to have one room fortified.’

Ivan holds a hand out helplessly. ‘With the sirens going off constantly, we end up living in just that single room.’

Elena elaborates that this is the reality for fifty percent of Sderot residents. ‘They end up living in just one room, and hardly venture out on the streets for fear of not being able to get to a bomb shelter in time.’

As we drive away, Elena informs me that Sderot has become the bomb-shelter capital of the world. ‘There are more bomb shelters in Sderot than any other place since world-war two.’

And, as if in support of that statement, an ambulance overtakes us, siren wailing; possibly in response to the red-alert sirens on the far side of the town ten minutes ago. Sirens wailing – whether from rocket alerts or ambulances, fire brigade or police – are omnipresent in Sderot. Of course, I’ve already heard the accounts from the other side that the rockets are homemade, inaccurate, and rarely kill anyone; but now seeing directly the terrible impact they have on a community, those come across as hopelessly lame excuses.

We pull over and start talking to a young taxi driver, Raul, waiting by his cab. Raul laments that Sderot is becoming like a ghost town through people’s fear to go out, and it’s hard on his business. He has three children who his wife stays home to take care of, but some months he admits it’s hard to put food on the table for them. Their house has devalued 25% in the past few years due to the rocket attacks, and they were already at the bottom of the price chain when they moved to Sderot. That was one of their main reasons for moving there; to be able to afford somewhere to live. Raul would like to move, ‘But where do we go?’ Everywhere else is more expensive, so that’s even further out of reach now for them.

There’s an underlying desperation in Raul’s tone. He’s in fact sympathetic with the plight of the Palestinians in Gaza, and doesn’t agree with the heavy military incursions from his government when they come, but points out that for people in Sderot it’s different. ‘The Gaza incursions when they come might be heavy-handed, but they last no more than a few days or a week. Here in Sderot we have the attacks day in, day out, every month and every year.’

Elena adds that feelings are often mixed in Sderot. Local people protest endlessly, why isn’t the government doing anything about this? ‘Don’t they care about us?’ Then when finally something is done, often they don’t agree with the action taken. And for the government, it’s a double-edged sword. ‘If they do nothing, they get the condemnation of the people in Sderot – but if they do something they risk international condemnation.’

Raul admits that he’ll probably in the end leave for the children’s sake, for the psychological damage that staying is having on them. ‘They try to hide it, but many days I see the fear in their eyes. It’s a constant pressure.’

But I see now that Hobson’s Choice in Raul’s eyes: on one hand alleviating that cloak of fear from his children, on the other wrenching them away from neighbourhood and school friends, plus the daunting prospect of meagre housing elsewhere or no roof over their head at all.

My next stop with Elena is a nearby coffee-bar. ‘Someone I’d like you to meet.’ We’re apparently early for them, so while we wait, she brings up a YouTube video on her laptop to show me. ‘And this is what Hamas feel about their rocket attacks.’

The video shows a Hamas leader on a rostrum, giving a speech to a large crowd in a square, forty-thousand plus. ‘The rockets are the way’, say the translated sub-titles. ‘Striking Sderot, Ashdod and, Allah willing, Tel Aviv.’ As he indicates the rockets flying over each time with a straight-armed thrust, it reminds me uncannily of a Nazi salute, the chanting crowd saluting back.

‘And while Ivan and Lena are stuck in their one room with the sirens wailing outside,’ Elena adds, ‘This is what they’re seeing on the news. You can imagine the psychological effect. Hamas know what they are doing.’

I’m tight-lipped, but privately my thoughts are raging: Possibly the most frightening message that could be sent to a nation built largely on holocaust survival. Akin to threatening a claustrophobic that you’re going to lock them back in the cupboard. I realize then that I’ve been terribly naïve with my report of a few years ago, have been guilty of only showing one side of the story.

The man who joins us for coffee minutes later, Adli, himself a Palestinian and a leading human rights advocate for his people, was previously attached to B’tselem. Elena informs me that he’s become respected by both sides of the conflict for his unbiased, yet searingly accurate reportage of events.

Adli is a good-looking man in his late-forties, the first shades of grey at his temples. Amiable and with an easy smile, but the burden of what he must have witnessed over the years is evident from the shadows in his eyes.

Adli has harsh words both for Israeli politicians and those in power in Gaza, Hamas. ‘Both parties are guilty of leading my people astray… and the people of Gaza and here in Sderot find themselves caught in the middle of this mess.’ Adli goes on to explain that one of his main complaints from his early days with B’tselem was regarding the accuracy of information, and often the guiltiest of ‘massaging’ information were his fellow Palestinians. ‘Very often I’d go to an incident where I’d heard that forty people had been killed, only to find that it was seven or eight. Or sometimes ten would become a hundred. Why exaggerate, I would admonish.’ Adli looks at me levelly. ‘And in my time with B’tselem, I heard many horror stories from fellow Palestinians about Israelis, particularly soldiers, which ended up not being true.’

I realize he’s talking about my account of Israeli soldiers occupying a house in Gaza and mistreating its Palestinian owner. I do a quick mental self-reprimand: it’s true, I hadn’t been there to witness any events. I’d taken the house-owner’s account – someone with a strong vested interest and axe to grind – entirely on face value.

‘Do you think the story I related of that Arab family might have been embellished or over-stated?’ I venture.

‘It might well have been. I think you should have checked first, possibly spoken to others. The account of olive groves and farm fields being bulldozed also seems a bit extreme. Little point in them doing that, and it’s also at odds with other accounts I’ve heard. You’re aware that when the settlers left Gaza, they left behind half of their greenhouses, almost four thousand in total, for Gazans to continue farm production and bring in much-needed income. Funds for which were provided by Jewish-Israeli agencies. But many of the greenhouses were damaged by Palestinian looters and militants, and became unusable.’

I’d heard some stories, I admit, ‘But I didn’t know the full extent of them.’

Adli smiles understandingly. It’s clearly not easy to take in all aspects of this conflict, as he has learned to do over the long years. I see then that Adli has my earlier report in his hand. He indicates one paragraph. ‘This figure of 120 homes a month demolished in Gaza, where did you get that from?’

‘From MSF and the ‘information adviser’ who accompanied us.’

Adli nods sagely, checking a detail in another file. ‘The actual figure is more like 120 in an entire year – closer to ten a month.’ He then methodically goes through and corrects all the remaining errors. The numbers killed were less than half the figure I’d stated in my report, and included many internal killings, the ‘infritada’, as it became known; plus many of the quotes from past Israeli politicians and military figures were also inaccurate or taken out of context.

I was incredulous. ‘Why would an organization like MSF pass on incorrect figures?’

Adli enlightens that they wouldn’t intentionally do that. But information out of Gaza is strictly controlled by the ‘information ministry’, and of course they have a great interest in amplifying those figures in their favour as much as possible. ‘MSF would have taken those figures in entirely good faith and passed them on to you.’

‘Rest assured, you’re not the first to have been caught out like this,’ Elena cuts in. She elaborates that one Jihadist web-site she’d recently come across claimed that 720 Palestinians were killed for each one Israeli killed. ‘And their claims regarding PST amongst children were as bad, which is why I showed you that earlier document.’ Elena passes across a page from a website claiming that 70% of the children in Gaza had been subject to ‘genocide’ by Israeli actions. ‘When I dug down, I discovered this referred to the actions of jets flying low over Gaza as a warning response to rocket attacks. This was without any firing of any sort, yet resulted in PST amongst a number of children in Gaza – which then became ‘genocide’ by the time it made it to this website.’

‘Demonizing Israel wherever possible has become a huge business,’ Adli adds, ‘and these terms – genocide, apartheid, ethnic cleansing – become the stock in trade of that. That’s not to say that Israel does no wrong, far from it – but in my opinion these terms don’t help. They just make matters worse for the Palestinian people.’

‘In what way?’ I ask, now somewhat concerned. I realize I’ve been guilty of bandying about some of these terms in my earlier report, and without even troubling to look at the other side of the conflict – the aim of my visit now to Sderot.

Adli explains that such terms are highly emotive and strike a strong chord, particularly among Palestinian teens. He shows me articles from leading Palestinian journalists decrying Palestinian leaders in both Hamas and Fatah for ‘trading in the blood of children and teens’ in order to further their cause. ‘This habit of our leaders to urge young teens to take martyrdom actions has to stop. It brings no honour whatsoever to our nationalistic cause.’

‘Palestinian teens are a particularly vulnerable group,’ Adli points out. ‘Often they’re urged by radicals to take up a rock-throwing front line against Israeli soldiers, some of them as young as twelve. Then older snipers concealed behind – callously and without any care – fire through that front line at the soldiers.’ Adli closes his eyes for a moment. ‘The outcome is predictable. The deaths are put down to the Israeli soldiers – cold-bloodedly killing children for doing no more than throwing rocks. Even those children catching bullets in the back from militant sniper bullets in the crossfire are put-down to the Israelis. It’s a one-way information war, with the intent of demonising Israel as much as possible. Sometimes they’re also urged by our leaders to take part in lone-wolf stone and knife attacks against sentry points or Israeli civilians – again with predictable results. News of their ‘martyrdom’ and more talk about Israeli ‘apartheid’ and ‘genocide’ urges the next young teen to take similar action and follow in their footsteps. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle.’

This time it’s me closing my eyes momentarily, as if in penance. I realize that apart from showing only one side of the conflict, I might have been complicit in fuelling the flames which has led to some Palestinian teens taking up such martyrdom actions. That hadn’t been my intention at all; it had been to raise awareness in the West so that pressure might be brought to bear on Israel from outside.

As I explain my initial aims, Adli consoles that, however misguided or unbalanced, my report along with others might have had some positive effect, ‘Because not long after Israel ceased their practice of destroying terrorist-family homes, and also disengaged from Gaza completely.’ He gestures towards the Sderot streets outside the café window. ‘Not that it did much good. Look at the rockets raining down. And right now there’s no Israeli occupation or presence in Gaza, so that can’t be used as an excuse.’

I nod solemnly, realizing the extent to which I might have been foolhardy in portraying only one side of the conflict.

‘Fair exchange is no robbery,’ Adli comments, and he passes me a transcript of an interview with a Hamas leader in which he openly admits that rockets indiscriminately target Israeli civilians, including many schools in Sderot. Clearly, it’s in answer to my earlier transcript from IDF sentry points. Elena has meanwhile cued some YouTube videos for me to watch. The first shows the death and destruction wrought by various suicide bomb attacks in Israel. I cringe. The Dolphinarium disco bombing photos are the most vivid and brutal, claiming the lives of 22 teens, some as young as 14.

‘You might have been guilty in your report of minimizing the brutality of these attacks,’ Elena suggests. ‘You mention simply that they’d happened, then appear to focus solely on the response of terrorist-suspect homes being bulldozed in response to such attacks – as if that was the more heinous act.’

Next Elena plays me videos from Palestinian children’s TV with bunny-rabbit figures instructing children that all Jews are evil, then jihadist sites with instructions of how to kill Zionists and Jews at every opportunity. I can’t help thinking of Ivan and Lena and others like them as I watch the videos. Escaped from the holocaust and now they must feel they’re once again surrounded by people who hate them and are intent on their destruction.

The final video Elena plays is an interview with Ahlam Tamimi, organizer of the Sbarro pizzeria bombing, which killed 15 people, including 8 children. As Tamimi talks in gloating terms about her joy when she learned that the death toll was higher than she’d first heard, a chill runs through me. While the reactions of the Israeli soldiers involved in the shooting of a girl on my earlier transcript were mixed – one pleading ‘don’t shoot her’, another later obfuscating and making excuses for his action – none of them came even remotely close to this level of gloating and joy at killing.

Picking up on my abject countenance, Adli comments, ‘If it’s any consolation, you’re not the first to be fooled like this, and you won’t be the last.’

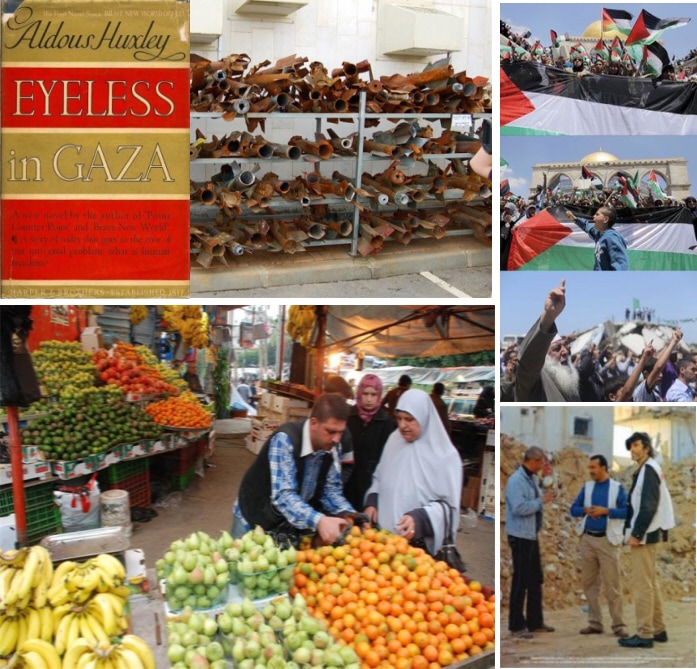

As if to elaborate, three days later, Adli takes me on a tour of Gaza. It’s a very different tour to last time. We see shops and shopping malls full of quality goods, market stalls full of fresh produce, high-end fashion and jewellery, the restaurants full.

Yes, there are still many underlying problems, Adli explains, and many of the products are black-market goods or smuggled in from Egypt. ‘But despite reports of a blockade, Israel still does its bit, with up to eight-hundred trucks a day full of food and provisions passing through the Sufa and Kerem Shalom crossings, including a number of luxury goods. The only restrictions are on explosives or potential bomb-making equipment. In addition, over 40,000 people pass each day into Israel through the Erez and other crossings.’ He shrugs. ‘And if you’re going to point the finger at Israel for the blockade, why not Egypt as well? The Rafah crossing was completely closed through most of the problem periods, and still is now. Or are we not allowed to criticize fellow Muslims, the blame always has to be put on Israel?’

I nod. There’s a side to this that perhaps I hadn’t previously appreciated. ‘So you’re saying that there’s an intended one-way slant to many of these critiques?’

‘Precisely. As with your last visit. You were shown certain things, one view of all the problems here, to show the suffering and support the ‘genocide’ and ‘apartheid’ epithets. As with all the other visitors given the same ‘tour’ – the Galloway’s, David Ward’s and Mia Farrow’s. Certainly, that side still very much exists. But why not show this side too?’ Adli waves one palm towards the shops full of goods and busy restaurants. ‘It’s a bit like taking people just on a ‘Ripper’ tour of London and its grizzly down-trodden areas with homeless tramps sleeping rough and drug-ridden council estates – but not showing them anything else. Visitors would be left with the impression that there’s little more to the city than mass-murderers, starving tramps and drug addicts. And I find that imbalanced, dishonest.’

As we pass some derelict buildings that have been the result of past Israeli missile or drone strikes, Adli gestures helplessly. ‘These should have been re-built years ago.’ Adli goes on to explain that enough aid and raw building material had been poured into Gaza to regenerate years ago, but reports were coming in that much of it was being used to build terror tunnels to bring in even larger rockets to attack Israel. ‘And I fear that Hamas’s hell-bent mission of constantly attacking Israel can only end badly for my people. The money should be used for building their welfare and future, not constant war which can only add to their suffering.’

My eyes linger on the half-bombed out buildings. The contrast to the buildings struck in Sderot, invariably re-built or patched up within days or weeks of rocket strikes. The need of Hamas’s ‘information ministry’ to keep the evidence of their suffering on display as a badge of honour, when in fact these buildings could have – from the vast influx of aid for building materials related by Adli – been repaired or rebuilt ages ago. An uncomfortable afterthought hits me: with the constant rocket attacks on Sderot, how much longer will the Israeli government stand by without intervening? I look at Adli.

‘You fear there might be worse to come?’

‘I do. I despair for my people – as I do the lack of balance and reason on both sides which has brought much of it about.’

I nod solemnly. ‘If I can write a more balanced article upon my return to London, one which shows both sides of the conflict, and more like me do the same – hopefully that will be avoided.’

‘Hopefully.’

But I can tell from Adli’s tone that he’s not holding his breath.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed