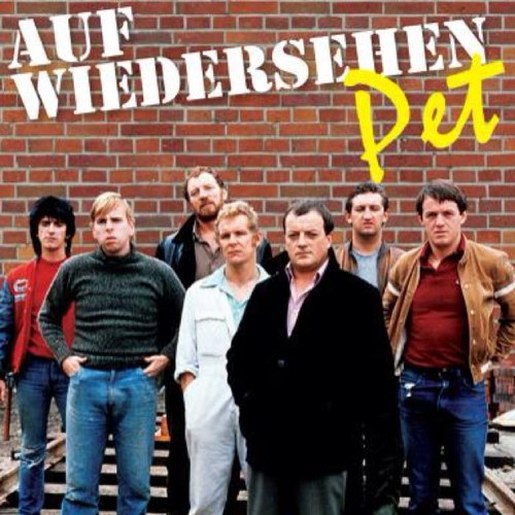

Telling the story of a group of builders who went to work in Germany, a number of them from the North-East of England, it appeared on British TV in the 1980s and went on to enjoy several series and re-runs, in the process making household names of many of its stars: Jimmy Nail, Tim Healey, Timothy Spall and Kevin Whateley.

Many I’m sure watched the series purely for its entertainment and comedy value without knowing the full background and history of the series, myself included – until years later when I embarked on a ‘Grand-Projects’ style self-build, and a couple of the builders on site did happen to know, because they’d been part of that wave of builders travelling to Germany for work in the late 1970s and early 80s.

Both at the time working in Surrey, one of them in fact was originally from the North-East, Sunderland, and had been a master-bricklayer for some 30 years, telling fond stories of building for various celebrities, including Tom Jones for his house in Weybridge. They also talked of what led to them both working in Germany for several years in the late 1970s and early 80s. The British building industry had fallen flat – many of its various slumps both before and since – and work for British builders was scarce. But there was work in Germany, with particular demand and good pay for bricklayers; and the main reason for that, ironically, was due to us bombing them in the war.

What happened after WW2 was that with extensive bombing of German cities, they needed rebuilding – quickly. Building in bricks was seen as too slow a process, so breezeblock and prefabricated-section building became the order of the day. But after thirty years of this post-war, as a result the skill of bricklaying in Germany had all but died – or indeed the generation that had been skilled in that pre-war had themselves died or were aged.

However, as Germany recovered in grand style and became more affluent, home-owners and many businesses did want buildings in brick again, and so they were forced to look outside to where those skills were still prevalent, mainly Holland and the UK. That call for labour from Germany in fact kept many British families clothed and fed over a vital period of a slump in the British building industry lasting almost a decade. My highly-skilled and industry-savvy bricklayer originally from Sunderland openly admitted that this ten-year work stint came as a godsend, and without it he didn’t know what he’d have done. We should also remind ourselves that this migrant labour force was welcomed into Germany with open arms, despite their virtually nil-German language skills (though I’m sure they arrived with a John Cleese style pamphlet reminding them: ‘Don’t mention the war’).

It’s a sober reminder that immigrant labour doesn’t always work one-way. German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the other day that there could be no access to the EU free market without also accepting the free passage of labour, and rightly so. After all, without it, the Auf-Wiedersehen Pet style migration of labour which had helped so many British builders during the 1970s and 80s wouldn’t have been allowed to take place.

A focus on the North-East in the TV series – and from the personal accounts shared from my pet-builder from Sunderland – became particularly ironic when I picked up the newspapers the day after the Brexit vote and saw headlines announcing: ‘Sunderland, the epicentre of the earthquake,’ with pictures of jubilant supporters held shoulder high and cheering wildly as the ‘Leave’ vote was announced. It makes one wonder if they’d be cheering so jubilantly if we were in the midst of yet another building slump and the announcement meant that their breadwinning-bricklaying partners would soon be on their way home to join the dole queue. Ironically, with a plunging pound and British business losing billions in the last week alone, that day might be closer around the corner than we think.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed